Blind and Sighted Pioneer Teachers in 19th Century China and India (revised edition)

M. Miles, West Midlands, UK.

PDF, 437 KB

SYNOPSIS

SYNOPSIS

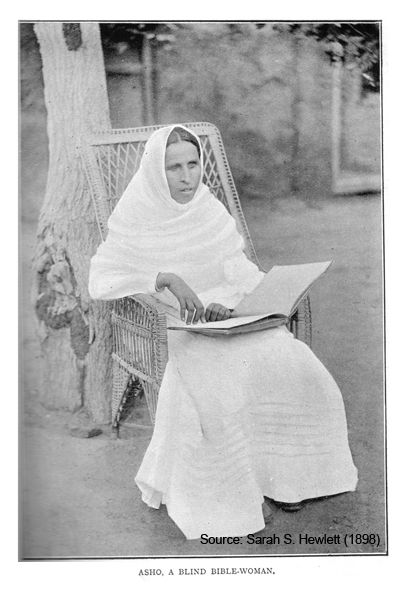

Blindness, blind people and blind teachers appear in literature from both Chinese and Indian antiquity. Legal and charitable provisions existed and a few blind characters played a role in epic history, while most blind Asians probably lived quite constricted lives. The 'official' starting dates for formal blind schools are 1874 in China, and 1886 in India, but in fact there was well documented educational work with blind people from the 1830s onward in both countries, and many aspects of it are both interesting and instructive for what came later. Two of the key 19th century special teachers were blind young women. In 1837, missionary teacher Mary Gutzlaff integrated several young, blind, Chinese orphan girls in her small boarding school at Macau. One named 'Agnes Gutzlaff' was then educated in London, and returned in 1856 to Ningpo, moving later to work in Shanghai. Agnes became the first trained and experienced person in China to teach blind people to read, using first the Lucas system, then Willam Moon's embossed script. She was a competent musician, and also supported herself by teaching English. Meanwhile, in the late 1840s, a class of blind adults received formal instruction from Rev. Thomas McClatchie at Shanghai. In 1856, Rev. Edward Syle opened a small industrial workshop at Shanghai for older blind people. In India, William Cruickshanks, blind since his boyhood at Madras, was educated with sighted boys. From 1838 to 1876 he was head of several ordinary South Indian schools. The Bengal Military Orphan Asylum, Calcutta, having blind orphans in its school, adopted the Lucas reading system by 1840. This was overtaken by Moon's embossed type for blind readers in several Indian languages during the 1850s. Missionary women such as Jane Leupolt, Amalie Fuchs, Mary Daüble, Elizabeth Alexander, Maria Erhardt, Emma Fuller, and their Indian assistants, used Moon script to teach blind children in integrated classes across Northern India in the 1860s and 1870s. The first regular teacher at an 'industrial school' for blind people at Amritsar was Miss Asho (later Bibi Aisha), a blind young Indian woman who had been educated in an ordinary school at Lahore. Asho read first Moon, then Braille, was competent at various handicrafts, and became adept at teaching other blind women and girls. Later accounts of the beginnings of formal education for blind people in South and East Asia have omitted the cultural background, several decades of 'casual integration' in ordinary schools, the early use of Lucas and Moon scripts, and the prominent part played by teachers who were themselves blind. This article describes the missing decades and people, with extensive reference to primary sources, and suggests some reasons for the biases and omissions in later accounts.

CONTENTS

THE HERITAGE FROM ANTIQUITY

2.0 Blind People in China's History

3.0 Blind People in India's History

4.0 Languages, Access and Interpretation

NINETEENTH CENTURY PIONEER TEACHERS: CHINA

5.0 Mary Gutzlaff at Macau

6.0 Edward Syle and Thomas McClatchie at Shanghai

7.0 Introducing the Protestant Work Ethic

8.0 Agnes Gutzlaff and Miss Aldersey at Ningpo

9.0 Agnes Gutzlaff, Useful at Shanghai

10.0 The Second Wave of Pioneers in China

NINETEENTH CENTURY PIONEER TEACHERS: INDIA

11.0 Beginning with Charity in India

12.0 Blind Students at Madras and Calcutta

13.0 Jane Leupolt of Benares

14.0 Miss Hewlett, Miss Asho & Other Pioneers in North Western India

15.0 Annie Sharp and Miss Askwith

16.0 Reflections

BLIND & SIGHTED PIONEER TEACHERS IN 19TH CENTURY CHINA & INDIA (revised edition)

1.0 Introduction

1.1 In both India and China there are records of blind people formally being taught to read in the late 1830s, and of blind people teaching others to read from the 1850s onward. The script invented in 1832 by Thomas Lucas at Bristol, England, consisting of embossed characters in the sort of symbols used by stenographers, was used in both China and India. Next the embossed type devised by the blind Englishman William Moon around 1847, based on modified characters of the Roman alphabet, gave strong competition to Lucas's 'shorthand' script. The system of embossed dots devised by Louis Braille during the 1820s and perfected by 1834, spread more slowly, and eventually overtook both Lucas's and Moon's systems throughout the world. [1] The teaching activities in China and India first took place with blind children 'casually integrated' in ordinary school settings. There were also formal efforts in both countries to teach blind people some income-generating handicrafts, at least as early as the 1850s. These activities were developing almost in parallel with developments in education of blind people in European countries. Though the Indian and Chinese starting dates were forty to fifty years later than the beginnings in France and England, developments in each continent were slow and the methods and technology were unsophisticated. They were so simple as to be transferable from West to East by missionary amateurs, with a modest amount of adaptation. The results were sufficiently positive to reinforce the process and to make some positive impact on attitudes towards blind people within a few local communities.

1.2 In both China and India, the history of the earliest blind and sighted pioneer teachers has been lost from both public and professional awareness. The first 'official dates' of education for blind people in India are usually given as 1886 or 1887, and in China as 1870 or 1874, when the 'first school for the blind' is said to have been started in each country by foreign missionaries. The present account recovers the detailed and fascinating 'missing history', with extensive contemporary documentation, and suggests some reasons why these records and activities disappeared from view. Trends since the 1950s away from 'institutional' education can in fact be seen as a rediscovery of the attitudes, practices and debates of the pioneers a century earlier.

1.3 Versions. Parts of this revised online version (2011) have been in progress intermittently since about 1996, taking advantage of the capacity of the web for revision and extension without being too solidly or prematurely 'fixed in print'. The first web version appeared in 1998 at the Catholic University of Nijmegen, which closed c. 2007; an early version of the material appeared on an ERIC microfiche; and the 'Indian' half formed part of a chapter in the author's doctoral thesis at the University of Birmingham in 1999. A brief polemical sketch of some aspects also appeared in print as part of a conference proceedings. [2] During the past 15 years, considerably more background information became available, and historiography of the fields involved became more complex and interesting. The current version appears to be about 50% longer than early versions, but part of the increase arises from adding the complete 'References' list separately, by authors' names alphabetically, after they have appeared scattered throughout the 'Notes'. Most of the 'revision and extension' occurs in additional details in the end-notes, so the structure of the main text is fairly similar to that of earlier versions, with some changes of nuance and interpretation arising either from additional information or the author's further reflection on the issues involved. There are unlikely to be any further versions, though some tweaking of errors may continue, as they come to notice. There remains infinite room for research in greater depth and detail of all parts of this vast new field, which hopefully will be taken up by scholars with greater competence, skills and range of languages.

2.0 Blind People in China's History

2.1 Blind people are recorded in Chinese antiquity as the beneficiaries of charitable institutions, and as court musicians. Details exist of the various ranks and positions of the musicians: they and their sighted assistants had specific seats on either side of the ruler, and used various stringed and wind instruments, drums and other rhythm-makers. [3] Helpful and respectful behaviour is described in the Analects of Confucius, towards blind music-master Mien, when he makes a visit. Confucius tells Mien when he has reached the steps, and when he has reached the sitting mat. After Mien is seated, Confucius tells him who is present in the room. [4] These social arrangements are from a period several centuries before Christ. The Guilds of Blind Musicians and Fortune-Tellers which functioned in China at least until the middle of the 20th century, claim a continuous existence back to 200 BC. [5] Across this huge span of time, a few odd dates on blindness can be placed from western sources. Mary Darley, a missionary at Kien-Ning in Fukien Province, reported working with people in a 'Blind Village' first established in the tenth century CE by a king whose mother became blind. [6] In the mid-fourteenth century, the traveller Ibn Batuta described a temple at Canton in which blind people received care, bed and board. [7] At Shanghai, William Milne visited a Foundling Hospital dating from 1710, in which there were some blind or otherwise disabled babies. [8] When Chinese historians seriously take up the field of disabilities, they will no doubt find much more detailed material from state documentation accumulated over the past 2,500 years. The few spots mentioned here merely indicate that activities in the 19th century inherited a very long and continuous cultural tradition of social responses to the needs and skills in blind people's lives.

3.0 Blind People in India's History

3.1 Blind people appear also in the literature of Indian antiquity. In the Rig Veda a person is deliberately blinded, but is said to be healed by the semi-divine twin Asvins. [9] The central plot of the greatest Indian epic, the Mahabharata, turns on the prohibition against blind Dhritarashtra becoming king. [10] This epic contains many references to visual impairment, such as Princess Gandhari's decision to blindfold herself, so as not to be superior to her blind husband. [11] Dhritarashtra did become king; but he later complained that, on account of his blindness, his eldest son treated him like a fool and paid no heed to his words. [12] An early 'industrial disability' was mentioned in the epic, when some priests' eyes became weak and painful from the continual smoke of burnt sacrifices, until they went on strike. [13] There was also a connubial quarrel, during which Pradweshi complained that her learned but blind husband Dirghatamas was unable to support her financially, so she had been obliged to support him. [14] Another learned blind teacher was Cakkhupala, who was depicted as taking a journey led by a sighted guide holding the tip of his staff; but later, in a familiar setting, he took his exercise independently. [15] The ancient Laws of Manu described various prohibitions on blind people, who were considered to be afflicted as a result of misdeeds in a previous life. [16] The Code of Kautilya aimed to protect blind people from insulting remarks. One could be fined for verbally scorning a man as 'blind'; but also for ironic use of a reverse term such as 'man of beautiful eyes'. [17] Chandra Roy, in a doctoral thesis on blindness in India, suggests that there was a civic and religious concern for the welfare of blind people in India as early as the 15th century BC; but he believes that this concern diminished during the Upanishadic period, when the pursuit of transcendental values was emphasized. [18] Nevertheless, early literature celebrates some individual social workers whose mission was to feed blind and other disabled people. [19] As in China, Indian history celebrates a small number of outstanding blind people. One of the best known is the 16th century poet Sur Das, possibly a court musician under the emperor Akbar. [20] However, Indian historical documentation seems to be scantier than that of China. Credible material is harder to distinguish from legend, and dating is often very difficult.

4.0 Languages, Access and Interpretation

4.1 Some 16th and 17th century sources with occasional notes on Asian disabilities exist in European languages, for example in Dutch and Portuguese - the latter more particularly in records of the activities of Roman Catholic religious orders at Goa and at Macau. [21] By the 19th century, English language sources are dominant, and some of them begin to reflect technical progress occurring in Europe, in education for blind people. The weakness of available historical sources in Chinese and South Asian languages, and the lack of European-language resource material in Asia, is suggested by unsatisfactory historical notes in recent publications, based on modern authorities. China's "first school for the blind" is said to have been founded in 1870, by "P.W. Moore"; or by "Pastor William Moore"; or in 1874 by "William Moon", or "Moon Williams". These dates and names are muddled or mistaken, probably in the transliteration from English to Chinese and back. Possibly the bookseller, publisher, evangelist and teacher of blind people, 'Pastor' William Murray, became "P.W. Murray", then "P.W. Moore", and was confused with the blind publisher and evangelist Dr. William Moon (1818-1894) of Brighton, England. Other sources err in suggesting rather more than was actually available, such as "schools for disabled people in China" more than a century before 1949, without supporting documentation. [22] However, five years of academic efforts to collect resources from across China have finally resulted in the publication in 2010 of three large volumes of historical source materials on special education, from antiquity to modern times, with a possibility of further volumes to come, which should encourage the growth of serious, evidence-based research in this field. [23] For India, the start of services for blind people is given mistakenly in almost all textbooks, as being in 1886 or 1887 at Amritsar. The blind historian R.S. Chauhan, of India's National Institute for the Visually Handicapped, recently tried to probe a little deeper, but reported his frustration at the dearth of materials. [24]

4.2 European sources, on which the present paper depends, naturally had an agenda influenced by European concerns. Nevertheless, if one is not blinkered by stereotypes of 'missionaries' or 'colonialism', it is possible to discern in the primary sources a range of thoughts and responses to blindness, not perhaps so different from those found in Europe in the 2000s. Within a few decades, however, the pioneers' thoughts and works were being tidied up by their successors, to give a polished picture of successful 'mission philanthropy'. Where the actual pioneers were not found apt for polishing, or where their historical records were not available, some of them simply disappeared from historical accounts, in favour of more acceptable, or better documented, 'pioneers'. The Europeans in China reported little of the thoughts and feelings of Chinese people; and when they did, it was of course at second hand. Nevertheless, it is possible to find in the 19th century material much that reappears with little change in the autobiography of a modern Chinese blind woman, Lucy Ching, from the 1930s to 1980. [25] Items such as the restriction of vocational training for blind people to courses in "massage and music" have continued into the 1990s. [26] The present paper, therefore, intends primarily to bring this 19th century material back into play, without trying to force it into any particular interpretative framework or theory.

4.3 During some 15 years since research was begun for earlier versions of the present article, there has been a slowly growing interest in histories of obscure or marginalised groups, a discovery of 'disability history' mostly in western countries, an interest in the part played by women in the colonial activities of nations such as Britain and the Netherlands, and other aspects of supposedly 'subaltern' histories, along with a 'critical' view of activities formerly seen as 'benevolent' or 'philanthropic', such as providing education for blind children with appropriate methods, either integrated with sighted children or in separate locations, or with a mixture of approaches. Such scrutiny is broadly to be welcomed; yet in the early stages of its growth, one may notice a heavy load of western theorising transposed into situations where westerners were working in Asian situations of which the modern theorisers seem to possess only the dimmest awareness now, and little if any awareness of the constraints and challenges experienced 100 or 150 years earlier. Before compiling the present sketch, the author, who is neither a woman, nor a missionary, could call upon twelve years' experiences of living in South Asia and developing services for children with disabilities during the 1970s and 1980s, at the invitation of Asian colleagues and organisations. Considering the varied difficulties and complexities encountered during this modern period of work, and learning later of the disability service development carried out by European and South Asian women in the 19th century, the author felt some recognition of the descriptions of what they had been doing, and considerable admiration for their achievements despite considerable obstacles, some of which seem to persist in similar forms to the present. Certainly some flaws can be noticed in the earlier activities, or in the way they were described, as well as there being flaws in the modern ones! Readers should make up their own minds how far they trust the evidence offered, and the framework in which it is presented.

NINETEENTH CENTURY PIONEER TEACHERS: CHINA

5.0 Mary Gutzlaff at Macau

5.1 Carl [Charles] Gutzlaff (1803-1851), the colourful Pomeranian pioneer missionary to China from 1827 to his death, is credited with having "rescued six blind girls in Canton", [27] and with being the founder of 'mission' to blind Chinese people. [28] What the 'rescue' consisted of, and how many victims came from Canton, is less clear. The blind girls, accumulating one by one, were certainly welcomed within Gutzlaff's extended household; yet the first, who received the name 'Mary Gutzlaff', had actually been found in Macau, after being kidnapped, blinded and maimed to make her a more pitiful beggar. [29] She was brought to Mrs Mary Gutzlaff, the missionary's second wife. [30] Another girl, 'Laura', was apparently brought to the Gutzlaffs by her father, after she had been blinded by her step-mother while he was away from home, again with the idea that she should earn her bread by begging. [31]

5.2 Reports by westerners of 'native barbarity' may always be treated with some caution; yet in the case of Mary, contemporary detail is given of a surgeon, Mr. Hunter, who operated successfully on her limbs, but could not restore her sight. [32] The missionary booklet giving this detail took pains to assure its youthful readers that "The Chinese are not savages... They are very polite people"! [33] Macau had had an Ophthalmic Hospital for a few years, run by T.R. Colledge, [34] which closed in 1832. [35] Nevertheless, the well-known surgeon Peter Parker of Canton also tried his skill on Mary's eyes, with some apparent success initially, [36] though the ultimate result was negative. John Robert Morrison, one of the most knowledgeable among the foreign community, was another contemporary witness of Mary's condition. He noted the painful frequency with which blind people were "condemned perhaps, irremediably, to a life of vice and ignominy: for the destitute blind of China are among the most depraved, and (lepers alone excepted) the most degraded class of outcasts." [37] In the case of Laura, she herself "was able to give an account ... of the last scene to which she was ever an eye-witness, her step-mother heating a knitting-needle, and with it and poisoned soap, robbing the helpless child she was bound to protect, of the inestimable blessing of sight. Laura could remember her father's return, the grief and indignation with which he beheld his mutilated child, the sudden and stern resolve rather to part with his little one, than to leave her in such cruel hands." [38]

5.3 Whatever melodrama may have accompanied the 'rescue' of these blind girls, the prosaic task of bringing them up fell first into the hands of Mrs Mary Gutzlaff, who as Miss Wanstall had gone to Malacca in 1832 as a teacher, and had married Gutzlaff in 1834, moving with him to Macau. She opened a small school there in September 1835, under the auspices of the Society for Promoting Female Education in China, India and the East (SPFE), with help from the Morrison Education Society. [39] Susanna Hoe suggests that the school at Macau "very soon concentrated its efforts on blind Chinese girls", [40] but this seems a little overstated. At the start there were "twelve little Chinese girls and two boys"; by December 1836 there were "twenty-three children", by March 1937 there were "twenty-six children, residing always with us", but in mid-1838 there were sixteen boys and five girls enrolled and boarding in the Gutzlaff residence. [41] It is unclear whether all five of the mid-1838 girls were blind, whether all were old enough to be 'in school', and whether among them all there were the "four little blind girls" mentioned by Mrs Gutzlaff in a letter dated October 4, 1837, thanking a Philadelphia friend for sending embossed books. [42] Certainly, the Gutzlaffs put two blind girls, Mary and Lucy, on a boat to London early in 1839, under the care of a nurse, [43] and soon after their arrival they were enrolled as boarders in a school run by the London Society for Teaching the Blind to Read. [44] Yet at the end of that year, William Milne mentioned "the 5 blind children under Mrs. Gutzlaff's care (now at Manilla)" [45] (They had decamped during the skirmishing between China and Britain over the opium imports.)

5.4 What seems to have happened is that Mary Gutzlaff, finding it hard to retain pupils at her school for more than a few months, realised that there would be no such problem with blind girls. [46] Morrison reported in July 1837, when there was only one blind pupil, that Mrs Gutzlaff was "anxious to increase the number of her blind pupils", but he did not favour the idea "until an adequate teacher can be procured". Clearly the number of blind girls did increase; and the remarkable picture appears of one of their fellow pupils, a 9-year-old sighted Chinese boy, teaching them to read their embossed books. He was Yung Wing [sometimes shown as Jung Hung] from a village on Pedro Island near Macau. More than seventy years later he recorded the curious chain of events by which he entered Mrs Gutzlaff's school, aged seven, noting casually that the three blind girls, Laura, Lucy and Jessie "were taught by me to read on raised letters till they could read from the Bible and Pilgrim's Progress." [47] A very young assistant teacher had in fact been in the pipeline from the SPFE, namely Theodosia Barker, who had briefly studied Chinese in London and had "also studied the system of instruction pursued at the Blind Asylum, which it is thought may be introduced with advantage into China". [48] Whether Miss Barker's preparation would have proved "adequate" was not seriously tested. She reached Macau in February 1838, but not long afterwards married an American missionary, Mr Dean, whom she accompanied to Bangkok. [49] This loss - of a sort that occurred not infrequently with the SPFE's female agents - may have enhanced the less than cordial response by the SPFE in June 1839, when they received a letter from Mary Gutzlaff, "stating that she had sent two blind children to the Society to be trained as teachers". The SPFE replied that its funds were not available for children's education, "even those whose faculties being perfect would afford the hope of their being hereafter useful, certainly not those whose infirmities could only render them a permanent burden." [50]

5.5 Mary Gutzlaff, though lacking specialist training, can certainly be regarded as a pioneer teacher of blind girls in China. The added merit may be claimed, that her school was both 'inclusive' and 'multicultural' - there is a certain charm in the idea of little Yung Wing busily learning to read a translation of ancient Middle Eastern scriptures (allegorised by the English tinker Bunyan, and printed in raised type in America), then passing on the skills and knowledge to three even smaller blind Chinese girls! Mary Gutzlaff could also be hailed as an early example of the adventurous young career woman, travelling east by herself, setting up schools, managing her home and profession independently while her husband distributed evangelical tracts along coastal China; and finally being deprived by later (male) historians of the credit for her benevolent work, which was automatically assigned to her husband. Alternatively, in the modern 'critical' fashion, Mary might yet come to be denounced by some as an exploiter who found it easier to 'control' blind girls than sighted children; who taught a 'colonial' curriculum of English and Judaeo-Christian propaganda, and tried to raise public support for her school by emphasizing the grisly fate from which she had rescued them.

5.6 Exactly what Mary herself thought she was doing, is now hardly to be known; but there was some public discussion of possible strategies for achieving the education of blind Chinese people, and thus rendering them potentially 'useful' - that key word of 19th century evangelicalism. Morrison in 1837 asked the London Missionary Society whether some missionary coming out to China might not "acquire in a few months a perfect knowledge of the system of teaching the blind?" More visionary, at that time, was his suggestion that "a blind scholar, himself well acquainted with the system - one imbued with true piety" might accompany such a missionary "as an assistant". [51] Although formal education for blind people in Europe was still then very restricted, and most blind Europeans lived in poverty and with minimal social status, Morrison was clearly capable of imagining a blind person providing technical skills to the mission, as well as contributing "true piety". His idea was also perhaps more realistic than the earlier suggestion by the ophthalmologist Colledge, that little 'Mary Gutzlaff' be sent to London for training, so that she should return as an instructress. [52] The latter plan was criticised on the grounds of the child's age - not because of any possible ill effects of a long voyage, different climate, food etc, but "on the score that she will forget her own language". Instead, it was proposed that "some two or three children, and an adult, may be sent from England, from the Blind Asylum, competent Teachers of the blind in handicraft as well as mental pursuits." [53] It is not clear how this would have addressed the issue, i.e. the need to find people who were competent both in Chinese languages and in skills to teach blind people.

5.7 The outcome was that two pairs of blind girls were despatched by sea, 'Laura Gutzlaff' and 'Agnes Gutzlaff' following Mary and Lucy, and being admitted to the London Blind School on the 3rd January 1842, "aged 7 and 5 1/2 respectively". [54] For two months, the school had four blind Chinese girls; but Mary died in March 1842, and Lucy in July 1843. [55] Before Lucy died, she and Agnes were able to demonstrate their skills at a 'Children's Missionary Meeting' on 29 March 1842. "Mr Thompson ... introduced the little blind Chinese girls. Lucy and Agnes were then made to stand up, and they read with their fingers from their raised letter books the 25th [chapter] of [the gospel of] Matthew. They read with great distinctness and propriety, but as their voices were weak, only those who were very near could hear them."

5.8 The language problem with the remaining two young children still defeated the stratagem of 'pairing'. A teacher later noted that "At first Laura and Agnes spoke their own language together, but after a time it was gradually forgotten, and at last became to them as a foreign tongue." [56] Meanwhile, Mrs Mary Gutzlaff had sailed to America with a further three blind Chinese girls, Fanny, Eliza and Jessie, whom she hoped would be trained as teachers and would return to China, "to convince the Chinese, that those who are deprived of sight, are not mere excrescences on the face of society, but that they can be taught, can in most cases support themselves, and can be useful and happy". [57] None of these three 'American' Gutzlaff girls did return; but at least one of them, Jessie, who died in 1915, had made herself 'useful' through several decades as a skilled proofreader of Braille publications, and earned enough money to endow a scholarship for the education of Chinese students in Shanghai. [58]

5.9 Of the London girls, Laura died at London in 1854, as a young woman of around nineteen years. She had spent many years as a learner; but also shared some of what she learnt. In 1857 a blind youth from Cornwall wrote, "There is an Institution forming here, and I am appointed one of the teachers. They wish me to teach Moon's system, which I have learnt, but I don't like it. T.M. Lucas's is the best system of all. I learnt it from Laura, the Chinese girl, when she visited Exeter nine years ago." [59] Laura would thus be counted among the 'useful' members of the human race. The continued history of Agnes, as a more remarkable pioneer teacher, will appear below in sections 8.0 and 9.0.

6.0 Edward Syle and Thomas McClatchie at Shanghai

6.1 If Mrs Mary Gutzlaff was the 'mother' of modern education for blind children in China, the 'father' of therapeutic industry for blind adults may have been the Rev. Dr. Edward W. Syle (1817-1890). [60] Syle was an Englishman who had a long and varied career as a missionary, much of it with the American Episcopal Mission at Shanghai. There, his work with blind people was done in friendly collaboration with the Rev. Thomas McClatchie (1814-1885) of the Church Missionary Society, and briefly with the help of the Episcopalian Rev. Phineas D. Spalding (1847-49). Syle was both a practical man and a scholar. The journal of his work, giving much thoughtful description of Chinese life and customs, was serialised in the Episcopalian periodical The Spirit of Missions. Syle was also the father of a deaf son. That experience may have increased his interest in people with any sort of disability. [61]

6.2 Looking back from twenty years later, Syle noted that the Shanghai Asylum for the Blind developed initially from the duty laid upon himself, McClatchie and Spalding, to act as almoners for the small Church attended by foreigners in the period 1845 to 1848. [62] Each Tuesday afternoon, some 60 needy people received a little money from the offerings made by the Church congregation, and listened to Christian teaching. Spalding recorded this duty on Tuesday, January 11th, 1848, saying "I have the halt, lame, blind, deaf, and afflicted in almost every way one can imagine". [63] On December 5th of that year the numbers were the same, and Spalding noted that eight or ten received the money at their homes, "as they are too old or infirm to come for it". [64] No doubt the majority of elderly disabled people were cared for and honoured by their own families at home, with the filial piety traditional in China. Nevertheless, in March 1849, one of the old men present at the weekly dole, after learning some Christian doctrine, demonstrated that judgements about personal 'usefulness' were not the exclusive preserve of Victorian evangelicals. He posed to Spalding a seemingly universal question of old age: "I am deaf of my ears, I am blind of one eye, and the other but slightly sees; I am lame of one leg, and I am seventy-four years old, and what use am I?" [65]

6.3 Edward Syle would soon concern himself with this question, especially when the almoners concentrated their charitable giving on blind people. Many tricks had been played on them to obtain money, and they were also worried about "the suspicion that we are ready to buy people to become believers". [66] They felt there would be less grounds for suspicion, "when the object of our charities are such a poor, neglected set of people, that their adherence to our faith does not seem to be worth having, even if it could be purchased". [67] Syle perceived in the blind recipients of charity "a langour, an inertness, a stupor... which convinced me that all we wished for had not been accomplished. ... what they wanted was 'something to do'; but what that something should be, did not so readily appear." [68] Enquiries were made into some common occupations of blind people at the time, at least in urban, coastal China. It was found that blind people were "largely employed as fortune-tellers; sometimes as guitar-players and ballad-singers; that some earned a few cash by grinding in the oil mill - going round and round in a circle of not more than ten feet diameter; and that others, more skilful, worked, during the cotton season, at cleaning the seeds from the raw material. Others again went about the street gathering old paper with writing on it, which they sold to a certain temple for burning." [69]

6.4 Syle was perhaps too kind to record the organised bands of blind and lame beggars, "raising their importunate and ceaseless din... pressing their claims upon the attention and compassion of the shopkeepers, householders and gentry" as described by William Milne at Ningpo, [70] or begging outside the temples; [71] Nor did he mention the commonly practised sexual exploitation of blind girls and women. [72] Syle did jot down a story of the powerful influence, on the Church accounts clerk, of a blind "strolling fortune-teller, casually passing by his door" who had convinced this superstitious man that he should not attempt anything in his life until he was 36 years old. [73] Syle's main concern, obviously, was to find feasible, worthwhile occupations for his blind people; but some time passed before he achieved this, among his many other duties, and with time away in America from early 1853 until 1856.

6.5 In the meantime, Syle recorded other data on blind people and service options. One day, the topic of good works and charitable institutions came up in the course of lessons with the most respected of the missionaries' Chinese teachers. Since it was known on both sides that the missionaries engaged in their weekly dole, Syle enquired whether it would not be possible for the teacher himself "to undertake to collect subscriptions and set on foot an Institution for the Blind, such as they are said to have at Soochow". [74] The old man replied that this would be immensely difficult, because only a wealthy Chinese would have the entrée to collect money from other wealthy men; and that anyway, much of the money collected for such objects was eaten by the collectors. Syle was surprised that this "heathen taking off the actions and reasoning of other heathens" should do so in a way "so singularly like the reasoning of the reluctant in Christian lands"! Syle himself was not over-burdened with social work theory or with good reasons for doing nothing. After expelling two poor boys from the mission's High School on the grounds of "invincible dulness", he found that he could not bear "to cast off the poor children", so arranged with his Chinese assistant for the boys to have their daily rice and a place to sleep while they attended another school. "This", he told his journal hopefully, "seems like a very natural beginning of an orphan asylum." [75]

6.6 Another illuminating story was recorded, of an elderly blind Chinese man who, after serving as a writer in the official Grain Department for 42 years, had lost his sight. Being now "a man half living and half dead", the old clerk complained that "I have no way of getting my living. If I had been an old servant in a merchant's house he would have fed me in my blindness and old age; but the mandarins are always changing about, and know nothing more of the men that serve them than that they do their work and get their wages." [76] Moved by the lengthy and harrowing account, Syle incautiously suggested to this blind man that he might see again - which then required the hasty but difficult explanation that spiritual, rather than bodily, eyesight was on offer. Eventually, Syle's own eyes were opened as it occurred to him that this matter might be communicated more effectively by one of the blind Chinese converts of the Church, a man named Yan-paon. He therefore introduced the two blind men, and left them to talk. [77] Further years elapsed before Syle perceived that all the poor, blind Chinese Christians might be 'useful' in distributing Christian literature. By 1856 he was noting that whenever they dispersed from the Church, they were given a handful of books for distribution and encouraged to bear witness to their new faith. Apparently the novelty of the situation brought many opportunities: "'A blind man carrying books!' the people exclaim. 'What can you want with them?'" [78]

6.7 The condition of blind people in general, "who are frequently left to starve in the streets", caused Thomas McClatchie to think of building an asylum, but he lacked the funds. [79] His first nine years of missionary labour, 1844-53, brought "the apparent result of ... 8 blind converts and one schoolmaster", [80] baptized only after lengthy instruction and scrutiny. [81] However, the conditions in which some blind Chinese Christians lived may have served to rebut the charge, already hinted, of their being 'rice-Christians'. Dr Fish, a physician new to Shanghai, described thus his visit to the dwelling of two of them: "A man suffering from fever and rheumatism, and totally blind, lay on a little pallet almost incapable of motion; while his wife, also blind, and very much emaciated, seemed to be suffering from disease of the heart. The house was a mere hovel, of the smallest dimensions, and without a floor; and as I cast my eyes around the desolate-looking apartments, it seemed hardly possible that two human beings, both sick and blind, could inhabit such an abode; yet here they have lived for years, and here they most likely will die." [82]

6.8 Hearing these two pitiful specimens talk cheerfully about their faith was described by Fish as "worth all the sermons I had ever heard". Another newcomer, the Rev. C.M. Williams, was moved by the sight of blind people at the Holy Communion service, who "with their long staves would feel their way to the rail, where they would kneel and receive the emblems of the Saviour's love." [83] Less elegantly, another missionary remarked that "We have a goodly number of them in our company today, and it is affecting to see them groping their way along". [84] Among them were some who managed to pull the wool over missionary eyes. The Episcopalian bishop at Shanghai, William Boone, had been very cautious in his baptism policy for professing believers, but was still forced within a year to denounce two blind 'Christians' as "arrant impostors". [85]

6.9 Less has been recorded of blind women at Shanghai, but one of the women missionaries managed to catch the authentic spirit of Nien-ka-boo-boo, a lively and intelligent old blind woman who belonged to the church and lived in a room at the Bishop's premises. One day, as this old woman was leaving her Christian instruction class, another woman in the class asked the Bishop for help with her rent. "Nien-ka-boo-boo, turning to the Bishop and laughing heartily, said 'Un sien-sang,' 'I dwell in my own house'." This was hardly a tactful remark in the situation, but the blind woman's "entire satisfaction in her independent circumstances" caught the witness's eye. [86] The missionaries often showed some ambivalence towards their elderly, blind, Chinese sisters. Miss A.M. Fielde, commenting on her work at Swatow in 1873, recalled how she had begun by teaching "five old, wrinkled, ignorant women"; then admonished her audience never to wait "until very suitable persons are found", since it might be God's choice to give them women who were "old, blind, bound-footed, degraded, stupid". This rather weak display of magnanimity was further diminished by Miss Fielde's hope that if you "make the best of them", God might kindly provide you with better material! [87]

6.10 Westerners usually took a poor view of Chinese methods of treating eye diseases. Mr Colledge, for example, writing of his ophthalmic service for the labouring classes at Macau, thought that "the utter incapacity of native practitioners denies to them all other hope of relief". [88] His view was endorsed by William Lockhart, another early western surgeon, who married one of Mary Gutzlaff's nieces and worked in China from 1838 to 1864. [89] On the other hand, it is interesting to read in a report on girls' and women's work at Shanghai, of a girl whose "eyes were in a very diseased state", for which "foreign medical aid was resorted to, but proved entirely ineffectual, and it was supposed that total blindness would be inevitable" - yet the girl's teacher noted that she was finally placed under Chinese treatment, after which her eyesight steadily improved. [90] The same teacher recorded an anecdote about one of her pupils, who had offended an old blind woman of the church, but then knitted some fine gloves as a peace offering for the old woman. [91] Such incidents make a welcome contrast with the tendency of later writers to present a bland picture of missionary 'good works' with compliant or even saintly blind people.

7.0 Introducing the Protestant Work Ethic

7.1 Employment, of a sort that missionaries could approve, finally began in 1856 after Syle noticed an old woman "twisting some long sedgy grass into strings, such as are used for holding together, by hundreds, the copper 'cash' which are in such constant use." He promptly asked her to teach his blind pensioners this modest craft, and "thinking, perhaps, that I was slightly deranged", she agreed. [92] Conversion of the blind people to the Protestant Work Ethic took a little longer. Syle put it to his future work force, especially the Christians among them, that they had kept part of the biblical Fourth Commandment - i.e. rest on the Sabbath; yet they had neglected the other part - to work six days. The point was conceded by the assembled blind people, with the proviso that they were "Poor, blind helpless creatures - how could they be expected to do anything!" Syle played his next card: they could make cash strings. The reaction was unanimous: "Such a thing has never been heard of." [93] The meeting adjourned, for a week of animated debate in tea shops and other places. At the next confrontation, a blank refusal to work was given by the blind people. Syle rebuffed this with the biblical edict, "A man that will not work, neither shall he eat". Those who wanted their dole to continue must learn to work; those who would not learn, should get no further dole.

7.2 Syle was far from being a capitalist 'grinder of the faces of the poor', and he seems to have won the day without ill-feeling. The pensioners "came to take a cheerful view of the whole thing, and were highly amused at the idea of blind people presuming to be 'operatives'." [94] Two rooms were loaned by the Methodist Episcopal Mission, and Syle recorded the opening of "this humble 'school for the blind'" on November 4th, 1856, with six apprentice string-twisters. [95] Within ten days, a dozen blind people were at work. The product range had doubled, as two of the workers knew from their earlier sighted years how to make the common rural straw-sandals. [96] The first batch of sandals was bought by Kiung Fong-Tsun, superintendent of a well-known Shanghai institution, the Hall of Universal Benevolence. Syle had invited this man, on the 11th December, "to visit my Blind School". A long and cordial collaboration ensued between the two men. [97] A week later, Syle received $100 from an American merchant, "towards carrying on my Blind School experiment". [98]

7.3 The industrial school soon required more space, and moved from the loaned rooms into "two apartments near our own (Episcopal) Church, also in the city". [99] Further crafts and customers soon followed. In November 1857, Syle found the blind people "picking oakum - an employment furnished them by one of the ship chandlers here, who is well disposed to assist in this matter." Another merchant quickly drummed up $500 dollars' worth of charitable subscriptions for the school. [100] By April 1858, the blind workforce was making door-mats from coconut fibre. [101] The missionaries were not content merely to keep idle hands busy. Bishop Boone, ordaining Deacon Tong-Chu-kiung on February 19th, 1857, advised that when he saw his brethren "sitting down in their industrial schools, and the blind industriously twisting their rope", he must read them some godly book, to "beguile their tedious hours, and enlighten their dark minds". [102] Syle's own voice and views dominate in the account of this industrial workshop - there is practically no other account. We do not know what the blind workers thought or felt. Syle tells us that, after a while, the workers had "brightened up wonderfully; and seem to look upon themselves as persons of no small consequence; members of a 'highly respectable community'." [103] The homes of many of them remained abysmal. Their working day may justly have been described as "tedious hours". Their pay was very small. Yet whatever it was, they were beginning to earn it by their own skill and labour, as their product range grew and found a market. Perhaps they did indeed begin to value themselves as people who were worth something.

7.4 After a few years, the work program faltered for reasons not fully clear. Syle himself spent several years as a pastor in America, after his first wife died in 1859. [104] There were financial problems in running the workshop at Shanghai, and political troubles in the region. Syle mentions the devastation of premises "by the rebel occupation of the city". [105] Further, the blind workers had not discovered the capitalist principle of 'built-in obsolescence' - their coir mats were strong enough to last ten years; they also lacked designer appeal. [106] Nevertheless, work was restarted in 1868 with 36 blind people producing mats sold for $215 during seven months. Three sighted workers were "engaged in purchasing coir, finishing the mats, selling them, and paying out the wages". [107] The 1868 annual report also mentioned receipt of reading material in Moon's script, "in the Vernacular of Shanghai reduced to alphabetic writing", which would soon be put to good use. [108] Syle was keen that "some new branches of industry should be cultivated", and during 1869 there was knitting for some adults, and a start on reading for others, using the Moon books. [109] He was clearly gratified that a newly established Chinese philanthropic work in the south west of Shanghai "would appear to have taken a hint from our method of operation, and to have introduced the working and teaching elements into their Asylum". [110]

7.5 Syle's industrial school continued after he left Shanghai for Japan, around 1870, but the financing was sometimes precarious. The work was left in the hands of the American Episcopalian Rev. Elliot Thomson. His report in 1873 refers to "a small balance in hand" and compliments the Chinese manager, Ze-lan-fong "for his energy and zeal in conducting the establishment". [111] Far on in 1914, the workshop was still functioning as modestly as when it first began, with "eleven old men and two women who knit stockings and make straw rope". [112] It was working in 1928, when Hawks Pott thought (mistakenly) that it had begun "in 1858", and was "more in the nature of a charitable than of an educational enterprise." [113] In fact, the workshop had served its purpose as a bridgehead, opening up work possibilities and experimenting to see what blind people could learn and do, at a time when expectations were minimal among both blind and sighted people of Shanghai. By 1931, Syle's imaginative, pioneering work would earn no more than a dismissive half-sentence from a missionary chronicler of services for blind people, who thought it was "not until about 1875 that work of a tangible nature was started"! [114] Thus 'small' was not 'beautiful' for writers in the heyday of the massive rehabilitation institution. Another fifty years on, when small neighbourhood centres with local community involvement were beginning to be better appreciated, Syle and his blind workforce had long disappeared from historical memory; yet the earlier documentation still exists, for those who are not convinced that the present generation is invariably wiser than all previous ones.

8.0 Agnes Gutzlaff and Miss Aldersey at Ningpo

8.1 Agnes Gutzlaff, sole survivor of the blind Chinese girls sent to London, completed 13 years of education at the school of the London Society for Teaching the Blind to Read. [115] At a missionary 'Farewell Meeting' in August 1855, she was commended to the port of Amoy (now Xiamen), for the task of teaching "her countrywomen, similarly afflicted to herself, under the auspices of the Chinese Evangelization Society", the organisation founded by Carl Gutzlaff. [116] Agnes was perhaps the first blind person of whatever nationality to be sent by a missionary society to another country. She was almost certainly the most technically competent person to go abroad on a mission to blind people. Twenty years earlier, J.W. Morrison had envisaged a (male) missionary learning to teach blind people, with a blind (male) assistant. [117] He could hardly have imagined a single blind, Chinese girl, aged about 19, undertaking both roles by herself.

8.2 Agnes left England presumably with great curiosity and some trepidation, for the country she had known only as a small girl. Her arrival at Hong Kong with John and Mary Jones, two missionaries partially supported by the China Evangelization Society, was quite inauspicious. The newcomers were accommodated temporarily by some German missionaries, for Mary Jones was about to give birth, and then all the Jones family were ill; the eldest boy died there of dysentery. [118] The Joneses and Agnes had originally expected to go to Amoy, but the destination changed to Ningpo (Ningbo), 500 miles further up the coast. [119] The Joneses had insufficient funds for the journey, and needed to be helped out by various missionaries. Young Hudson Taylor, who would later found the China Inland Mission, wrote home disapprovingly to his mother about the arrival of the impecunious Jones party, with Agnes lumped in as extra baggage: "By some means he, his wife & remaining three children (the last four very unwell) & a blind Chinese girl (!) arrived in Shanghai. They were kindly received by Mr. Wylie - had not money to go to Ningpo. ... As you may suppose this has caused no little sensation." [120]

8.3 Hudson Taylor's own financial arrangement with the China Evangelization Society was shaky, [121] which seems to have made him the more irritable with other people's apparent improvidence. The Joneses had no guarantee of support from that Society, merely a promise of help as funds permitted. Taylor thought this was bad enough, "without having taken additional charge" of Agnes, who had only £10 per year promised for her support. Patrolling the financial, social and racial boundaries of his time, Taylor remarked "how very wrong it is, to take a poor blind beggar girl, bring her up in the best style, & then leave her with a less sum than will [nearly? meanly?]* pay for her food, for she cannot now live as a Chinese." [122] *[handwriting unclear]

8.4 However, Ningpo was reached at last. Agnes was welcomed by Burella and Maria Dyer, two young missionary teachers working with Mary Ann Aldersey. [123] In 1844, Miss Aldersey, a woman of independent means and "the most famous lady missionary of those early days", had opened, at Ningpo, what the foreigners believed was China's first girls' school. [124] Her reception of Agnes in June 1856 was positive: "Last Saturday, we received an interesting addition to our teachers in the arrival of Agnes Gutzlaff, whom Mrs Gutzlaff, many years ago, rescued from heathen wretchedness". [125] The stock phrase recurred as Aldersey noted Agnes's education at the hands of her Christian teachers, "preparing this blind girl, through a course of years, for usefulness". Agnes, weary no doubt of being part of the Joneses' baggage, showed herself "very desirous of commencing some work of usefulness immediately". She was introduced to a girl in Aldersey's school who had become blind after her enrolment. A similar girl from another school had been invited to attend, and Aldersey planned to "fill up a few vacancies" with further blind girls. There would be plenty of opportunity for 'usefulness'. [126]

8.5 Miss Aldersey, locally known as the "Witch of Ningpo" and credited with magical powers, often had trouble attracting and keeping pupils - why should this well-to-do lady leave her own country to teach other people's children, unless sinister motives lay behind it? [127] Some local suspicion undoubtedly transferred to Aldersey's new protegée. A class of blind adults could not quickly be found, even by a visit in April 1857 to a local asylum, "one of the few places supported or aided by Chinese charity". [128] Yet this modest pace of development also gave Agnes time to learn the Ningpo dialect. Aldersey further noted in January 1858 that not all the younger pupils were ready learners. Ching Vang, a blind girl, "was very untoward for some time; so much so, that, to avoid unceasing annoyance to Agnes, I contemplated sending her back to her parents." Agnes must have persevered, for Ching Vang later professed Christianity and her teachers continued "training her for future usefulness". [129] Agnes was teaching three blind girls at this time. [130]

8.6 The issue of Agnes's linguistic abilities is interesting, because some later mission chroniclers believed she was "unable to do much to help the blind owing to ignorance of the Chinese language and customs". [131] Even at the time, Hudson Taylor wrote dismissively that she "plays well on the piano-forte, has been brought up in the drawing-room, & knows nothing of Chinese". [132] The suggestion of language incompetence is directly rebutted by an independent contemporary witness, who reported in 1859 that "Agnes had little difficulty in acquiring the language, was able to speak with great facility at the time I was at Ningpo, and it pleased God to bless her labours". [133] This view was endorsed by Miss Aldersey. Fond as she was of Agnes, Aldersey was also a woman of intelligence and discernment, unlikely to be misled over such a basic requirement for evangelistic usefulness: "You will be pleased to hear that Agnes (whom I love very much), being now able to speak the colloquial, is making herself very useful in a School of Industry for the Blind, which I have established in the midst of the city. She spends the whole of every morning there, teaching by word of mouth, and in some cases by the raised character, hoping that sooner or later, the seed sown may take root." [134] The second industrial school for blind people is thus incidentally placed on record, starting within two years of Syle's school at Shanghai. As in the latter, Aldersey's blind people made "string, straw shoes, and sandals. One or more can knit the coarse socks for the Chinese. The chief employment hitherto has been making mats". [135]

8.7 From this period, an open letter from Agnes Gutzlaff survives, "written in English by Herself" to her friends in England. She began of course with 'usefulness': "I have been longing to write and let you know of the sphere of usefulness God has opened for me in mine own country. Miss Aldersey has a working institution in which she employs the blind at her own expense; they come every day from nine to five. They make mats, straw shoes, stockings, and a kind of string. We have at present eleven workers in the Institution. I go every morning at nine. I teach them reading, and speak of the only living and true God; also of Jesus, who is the only Saviour of the world. ... In the afternoon, I teach four girls in the house." [136]

8.8 This was by no means the whole of Agnes's work. Miss Aldersey had earlier mentioned a regular "two hours' trip on the canal from this city" to visit a blind woman whom Agnes was teaching to read. [137] There were other rural trips, in which Agnes was something of a spectacle - a blind woman, of Chinese appearance but dressed as a 'foreign devil', reputedly able to read books with her fingers, and accompanying a well-known witch... "A month ago I went with Miss Aldersey into the country, to a place called San Poh. We were there only a few days, and each day crowds came to see us. One day I went to call on a Christian woman who was ill; as soon as I got there, a large crowd gathered round the door, and almost would have done mischief to it, because they could not get in to see me: for the room was too small to do so. I left quickly, and when they got a peep at me, they exclaimed, "Oh, she is really a human being!" [138]

8.9 Agnes probably traded on the public spectacle, in aid of 'usefulness'. William Moon had sent out copies of St. Luke's Gospel embossed in the Ningpo dialect, and "a young woman" at Ningpo, i.e. Agnes, "frequently sat in the Market-place and on the steps of the Idol Temples (where numbers of persons congregated), and there read the Gospel narrative to the assembled crowds of surprised and attentive listeners." [139] Behind this exhibition lay a 'battle of the types'. The London Society for Teaching the Blind to Read had earlier sent "part of the Gospel of St. John to Miss Aldersey" in Lucas's script, which Agnes had learnt and used at the Society's school in London; as well as sending "a ciphering board and type" at Miss Aldersey's request for the use of their indefatigable former pupil. [140] Agnes, however, had by now taught herself to read Moon's embossed type. [141] She preferred the Moon version and must have advised Miss Aldersey of its superiority, because the latter also reported to the other Society, supplying Moon's books, that this was her own "decided preference". [142]

8.10 By the end of the 1850s, Miss Aldersey was ageing and weary. With Agnes and a few others, she had been living with the Rev. and Mrs. Russell of the Church Missionary Society, [143] and planning her retirement. After 23 years' work in China, she went in 1860 to Australia, leaving her schools to be run by the American Presbyterians; but "the school for the blind, under the charge of Agnes Gutzlaff, the blind native teacher ... still depend upon her for support." [144] From Adelaide, Miss Aldersey wrote to thank the Russells for their kindness to Agnes, and to ask for continuing "protection and guidance" from C.M.S. missionaries towards her. Miss Aldersey guaranteed that Agnes would "at no time be an occasion of expense to them", undertaking that she and her heirs "shall be responsible for necessary expenses which the Christian public may sometimes fail to provide for". [145] A special note was enclosed about the association of Agnes with the German missionaries of Hong Kong. Aldersey was anxious that Agnes should not be handed over to them, "or to other parties, who might perhaps fail to appreciate her and her services as we do." [146]

9.0 Agnes Gutzlaff, Useful at Shanghai

9.1 At the time of Miss Aldersey's departure her colleagues at Ningpo faced the increasing political turbulence that had been spreading across China; and news of Agnes's activities became scarcer. She was still teaching at Ningpo in 1861, [147] and the Rev. William Russell appreciated her musical talents. As well as supervising her blind industrial school, Agnes led a singing class "for those members of our Church who have an ear and taste for it, with a few of our schoolboys; so that by this means we have been enabled, during the latter part of the year, to have the praises of God sung as well as spoken in the native church". [148] However, this harmonious situation did not last. An evangelical magazine in England reported in October 1862 a letter received from Mr Russell stating that "on the capture of Ningpo by the Taeping insurgents, he and Mrs Russell were obliged to leave the city and to send Agnes Gutzlaff to Shanghai, where she is conducting an Industrial School under the superintendence of the Rev. John Hobson". Yet in fact, some months before that was published, the Rev. Hobson, who had been British Chaplain at Trinity Church, Shanghai, died while on a visit to Japan. [149] It seems very likely that Agnes worked initially at the Industrial School founded by the Rev. Edward Syle at Shanghai; but Syle and his family were no longer there when Agnes arrived. After the death of his wife in 1859, Syle returned to the US with his children in December 1860, took charge of a church in Philadelphia, and married again. The blind people's organised light industry came to a halt at some time after the Taiping forces occupied Shanghai and in the subsequent fighting which led to their defeat in 1864. After some years' work in the US, Syle returned to Shanghai and reported in June 1868 that "Both ground and house have recently been put in order, after the devastation caused by the rebel occupation of the city. Work also (which for some years was intermitted) has been resumed..." [150]

9.2 In those intervening years, news of Agnes appears only in brief summaries, unless new material may yet become available perhaps from Chinese sources, or unpublished correspondence. Miss Lydia Fay, the American missionary and scholar of Chinese literature, noted in 1866 that "I see Agnes Gutzlaff occasionally" at the Chinese church in the city, but that Agnes had been ill; and the possibility of Agnes playing a harmonium at the church was mentioned. An article in 1867 about "The Blind Chinese Teacher" has an engraving from a photograph of Agnes (taken in 1855), but adds no new information except that she was "still usefully employed in imparting to others the instruction which she has found so valuable to herself". [151]

9.3 Finally, a resumé or obituary appeared in London in 1878, describing Agnes's life at Shanghai, though it does not give the date of her death: "She resided at Shanghai, in a native house, retaining the European dress; and in order to enable her to converse with the inhabitants of that district had to learn the Ningpo and the Shanghai dialects. Her employment was that of a teacher of English to the educated Chinese. She was much respected by all classes, and had the entire confidence of her countrymen. As an instance of this the Committee are informed that after the Tai-ping rebellion had been quelled, and every known rebel had been executed, a history of the nature of the rebellion and of the religious tenets of the Tai-ping-Wang was desired. Application was made to Agnes Gutzlaff, who, knowing that implicit confidence might be placed in the honour of the inquirer, soon found out a member of the body who gave the desired information." [152]

9.4 Perhaps some of the earlier points in this testimonial influenced later writers to think that Agnes had been of more use to English culture and the upper classes than to her fellow blind people; but it would be unreasonable to doubt her ongoing work for blind people. She was not only the first well-trained teacher of reading for blind people in China's long history, [153] but as a role model Agnes was unique - a blind young woman living independently and mostly paying her way by using the skills her education had provided. Apart from the well-to-do who could pay for English lessons, the whole pattern of Agnes's life would suggest that she probably continued serving the poor and needy, whether blind or sighted. At the same time, perhaps the later point about making contact, through Agnes, with someone having inside knowledge of the Taiping beliefs, caused uneasiness in some western minds. Her position seems to have been liminal throughout her life, on the edges of Chinese society and of English society and of the 'sighted' world. Yet the resumé concluded that Agnes "worked hard, lived sparingly, and saved money, and at her death her property was left to found a hospital called by her name." [154]

9.5 In the absence of more precise information, the 'Gutzlaff Hospital' (also sometimes known as the 'Gutzlaff Eye Hospital', or Gutzlaff Native Hospital') gives possible clues to the close of Agnes's life. From blind beggar girl, to teacher with £10 per year, to founder of a hospital, seems almost a 'rags-to-riches' outline, without disclosing where the 'riches' came from, or their size. Agnes's savings from several years of teaching were probably augmented by gifts or a legacy from Miss Aldersey, from local sources, and perhaps from sources in England. Like its founder, the Gutzlaff Hospital was a place of modest pretensions but undoubted usefulness. During a discussion in 1874 of the future of a different hospital, the "Gutzlaff Eye Hospital" was said by Mr Egbert Iveson to be "located in the property in Ningpo Road which formed Miss Gutzlaff's bequest for the purpose, but had to depend on external sources of income". [155] It was open by the end of 1871, for in September 1872, Dr Alexander Jamieson reported on his "nine month's daily attendance upon a large number of outdoor patients at the Gutzlaff Hospital". [156] Half a year seems a credible period, following Agnes's death in June 1871, for the legal formalities of her legacy to be processed and for her trustees to collect working funds and arrange staff and basic equipment for a small hospital. [157]

9.6 How the Gutzlaff bequest came to be sometimes called an Eye Hospital is unclear. [158] Agnes quite likely wished that ophthalmic work should be prominent; but there is little evidence that it was. Jamieson's half-yearly Reports on the Health of Shanghai regularly gave details of cases he treated at the Gutzlaff Hospital from 1872 to 1883, but none involved eyes. [159] Surgeon Henderson, who was Jamieson's contemporary, noted that eye diseases were "the commonest and most largely represented in the Shanghai Native Hospitals", and discussed these problems at length; yet the sole case he mentions at the "Gutzlaff Native Hospital" was one of a facial tumour. [160] From c.1871 to 1876, a room at the Gutzlaff Hospital was "hired by the Municipal Council as their vaccinating station at a rent of $150 per year", which must have been contributed very usefully to running costs. [161] This reinforces the picture of the Gutzlaff Hospital as a small, low-budget, general-purpose institution, "in one of the back streets of the English Settlement", [162] where Chinese people came with the usual range of outpatient diseases and various orthopaedic and obstetric problems on which Jamieson operated. Eye work very probably did take place, but of so routine a nature that Jamieson found nothing worthy of publication.

9.7 By 1883, the trustees had implemented an idea that had been considered for several years, to amalgamate the Gutzlaff Hospital with the new St. Luke's Hospital (formerly the Hongkew or Hongque Hospital), and thus "to lessen the number of Hospitals - there were then some that were small and struggling", among which was clearly their own. [163] Proceeds from the sale of the Gutzlaff Hospital's effects gave St. Luke's "a piece of land on which the present out-patients department stands", and with which the Gutzlaff name should continue to be associated. The name was indeed orally transmitted as far as the 1930s, where it appears in Wong & Lien-Teh's monumental History of Chinese Medicine; but the key role played by Agnes had disappeared. [164]

10.0 The Second Wave of Pioneers in China

10.1 As Agnes was disappearing from the scene, William Hill Murray (1843-1911), a one-armed colporteur with unusual talents in memorisation and language learning, was employed with the National Bible Society of Scotland. He arrived in China in 1871, spent some months learning Mandarin at Chefoo, and in 1873 was based at Peking (Beijing). In the course of his colportage work he began to notice many blind men who were interested to have some part of the Bible, in the hope that someone would read it to them. (Had Murray met Agnes Gutzlaff, she could have given him much information about the earlier history of blind Chinese people reading the Bible). After struggling for some time to discover a way to make Bible reading easily accessible to blind people, and unsuccessful efforts to interest missionaries in this idea, Murray finally hit upon a method based on Braille, made some experiments around 1877-78, and late in 1878 he was beginning to teach one or two blind men and boys. Murray himself had learnt (or improved) his Braille at Peking along with the blind daughter of a medical missionary, little Miss Mina Dudgeon and her teacher, Miss Chouler. By the time he had four blind students, early in 1879, he was visited by the traveller and writer Constance Gordon-Cumming, who was delighted by what she saw and heard, and later took it upon herself to tell the world of Murray's remarkable work. [165]

10.2 Murray's small beginning of education for a few blind men and boys in 1879 would later become the Beijing Blind School, one of the leading national centres in the 2010s. [166] It was followed in 1883 by the Hankow Blind School, foundation of which is now attributed to David Hill - though it was the somewhat eccentric zealot Pastor Crossette who collected the first blind boys, and who revised Murray's system of Braille for the Hankow dialect. [167] Work was begun in 1889 leading up to the foundation of a school for blind girls at Canton, from which Dr Mary Niles was later credited with opening "the first institution for these unfortunates in China", [168] - though, once again, it was a blind Chinese woman who actually did the teaching, [169] and any earlier work with blind girls was ignored.

10.3 William Murray, David Hill and Mary Niles have repeatedly been honoured by 'popular history', as the founders of education for blind people in China. The pioneering efforts of earlier workers such as Mary Gutzlaff, Thomas McClatchie, Edward Syle, Miss Aldersey and 'Agnes Gutzlaff', are clearly documented from primary sources between 1837 and 1870, as shown here; yet they still await recognition. It does no service to China to omit nearly 40 years of documented work teaching and training blind children and adults before Murray started his school.

NINETEENTH CENTURY PIONEER TEACHERS: INDIA

11.0 Beginning with Charity in India

11.1 Formal European charitable work in India began in the 16th century with some Portuguese hospitals, [170] and continued with a modest poor fund at Madras, first for European distress, then for the native poor. [171] Compared with China, the long years of slowly growing British influence in India gave a different background to work with blind people. Some formal contact was developed a few decades sooner; yet the evidence suggests that it followed a similar pattern of early charitable donations and ophthalmic surgery, [172] then the education of some blind children in ordinary schools, facilitated by the advent of reading materials using the embossed scripts of Lucas and Moon; with later on some residential asylum or orphanage schools and finally the use of Braille.

11.2 In 1800, when outdoor relief in England was still poorly organised, the Indian Presidency Governments hardly expected to solve "the problem created by the vast number of beggars in India... for many of whom poverty was the result of some physical disability". [173] However, missionaries personally exposed to disabled beggars were not always willing to see the Government escape all responsibility. For some of them, "close acquaintance with Indian conditions turned missionaries from pious evangelists to fearless 'radicals' and people-protectors." [174] By 1802, William Carey, Joshua Marshman, William Ward and others at Serampore were giving weekly alms to blind people and lepers; but were also beginning to campaign for more formal service provision. Carey was involved with others in starting a leprosy hospital. For this, land and a substantial donation were received in 1818 from Raja Kali Sunkar Ghosal, one of a family that had long collaborated with British charitable efforts. [175] The Raja also opened a blind asylum at Benares in 1826, after arranging "with considerable difficulty and expense" for a survey to be made of blind beggars and their needs. [176] This survey found 225 blind men, of whom 100 had been born blind. It was also discovered that the majority of blind beggars had existing 'domestic ties' and would not wish to reside in an asylum, where they would not be allowed to go out begging. [177]

11.3 As these early essays in institutional care began, the practice of a weekly dole for blind and other disabled people continued in many towns. At Cawnpore [Kanpur] in 1809, Henry Martyn preached and gave money each Sunday to a crowd of "the blind and the deaf, the maimed and the halt, the diseased and the dying". [178] At Allahabad, in 1826, Mr. Mackintosh read the Bible regularly to 250 lame, blind and indigent persons, and distributed alms to them from a regular collection among the local Europeans. [179] In 1839, at Benares, William Smith preached weekly in a chapel crowded with poor people, "of whom a number were blind and lame", before giving out alms or food. [180] Around 1857 at Rutnagherry, 160 miles south of Bombay, de Crespigny noted that "The lame, the blind, and the deformed receive allowances from a charitable fund supported by the European community". [181] In fact, dole and preaching lasted to the end of the century. At Agra in the 1890s, a religious service with alms distribution organised by Dr. Colin Valentine for the poorest people, grew into a church with several hundred attenders, "of whom nearly three hundred are blind". [182]

11.4 The great majority of blind people undoubtedly lived at home, sharing in whatever living resources were available to their family - which, in times of scarcity, might be hardly enough for survival. [183] Of the rural majority, very little is known, since such comments as were recorded about blind Indians were mainly about the 'visible problem' of blind beggars in urban areas. District Officers occasionally noted traditional rural measures. For example, among the Garrows in north-eastern India most villages were said to have had "a lame or blind person, incapacitated from other work, who invokes the deities, and offers sacrifices for the recovery of sick persons." [184] Among the Yusufzais along the north-western frontier, Bellew noted that the distribution of alms was "very generally observed by all classes according to their means. The priesthood, widows, orphans, maimed, blind, aged, &c., are the recipients." [185] Wealthy Indians continued throughout this time to make charitable donations and provide food for poor, blind or otherwise disabled people in the traditional manner. The occasional massive display of bounty occurred, tending to reinforce European doubts about the whole process. "Dwarakanath Tagore made a startling announcement of a big donation of Rs.100,000 to the [District Charitable] Society in 1838. ... The Europeans were naturally stunned, and so were the Indians. ... the amount was utilized by the Society, according to the wish of the donor, in establishing the 'Dwarakanath Fund for Poor Blind'." In 1840, 214 blind people benefitted from the Dwarakanath Fund. [186] Whether the soul of Dwarakanath Tagore benefitted in his next incarnation is nowhere documented - but this was the motive often cynically attributed to charitable donations in India, together with the name and fame of being a philanthropist, though sometimes benevolent sentiments were also considered as a possibility (somewhat earlier than the western fashion for incredulity toward philanthropy). [187]

11.5 Conscious of the limitations and dangers of merely doling out money, some missionaries attempted to rouse public awareness and tackle some of the roots of poverty and distress; yet with very slow results. Meanwhile, the next phase of campaigning by practical example involved opening educational institutions; in which there were undoubtedly some Indian children with mild to moderate disabilities casually integrated with their classmates. In the earlier part of the century, such children tended to appear merely in parenthesis. Thus the Rev. Charles Leupolt, to whom the famine of 1837 delivered hundreds of orphans, reported that "We have at present 121 boys, divided into several classes. They all, with the exception of a few blind, dumb, idiot and sickly boys, read the gospel." [188] The lowly status of work with blind people continued. In 1881, for example, a visitor to India noted that his host, the Rev. Francis Heyl, was running "an important educational establishment with an average attendance of 116 scholars"; adding as an afterthought that Heyl had "also the care of the Blind Asylum in Allahabad." [189]

11.6 Hundreds of thousands of people died in the 1837 famine, and the missionaries could not easily forget the state in which orphans arrived. Chambers described a scene at Agra, echoed or amplified in all the subsequent famine reports: "The children, when first thrown on us, were a most harrowing spectacle - emaciated skeletons, the skin shrivelled on their cheek bones, so that they looked like very aged men and women: half clad, as most poor children are, their ribs stood out prominently, like the bars of a grate. In such a state of inanition were they, that it was necessary to feed them at first by a spoonful at a time." [190] Many of these children soon died; some continued for a few months; some survived, but with lasting damage. The Rev. John James Erhardt recalled that among the first 330 famine orphans at Agra, many became blind through disease allied to overcrowding and low resistance, until eventually better premises were found at nearby Secundra. [191] The actual daily care of these children fell, of course, into the hands of missionary wives and their Indian assistants, which further contributed to its modest or absent status in historical accounts.